Most developers start with prompting the same way: write a clear instruction, send it to the model, and tweak until it works.

That approach looks great…

…until it doesn’t.

As soon as tasks require structured reasoning, multi-step planning, or tool interaction, naive prompting breaks down. Outputs become inconsistent. Reasoning collapses. Latency rises. Costs increase.

This is where advanced prompt engineering techniques change the game.

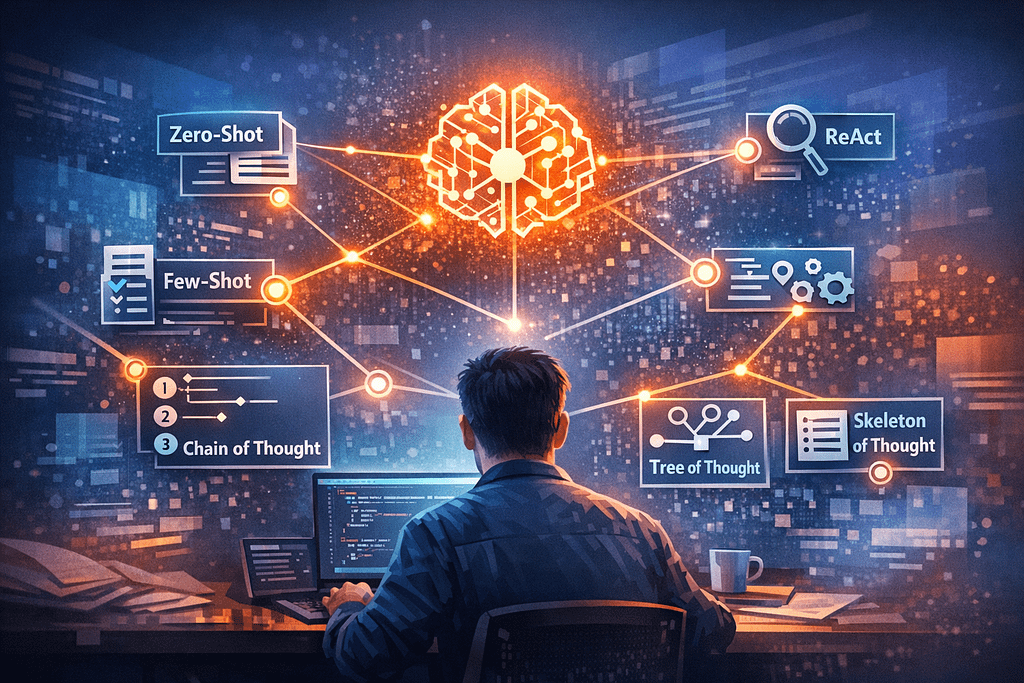

Zero-shot, few-shot, chain-of-thought, Tree of Thought, Skeleton of Thought, and ReAct prompting aren’t just stylistic differences. They represent fundamentally different ways of shaping model behavior, especially how it plans, reasons, and decides what to do next.

If you’re an experienced developer new to AI, think of prompting like API design. The structure of the request determines the quality of the system’s response. Advanced prompt engineering techniques are about designing prompts that guide reasoning (not just generate text).

In this guide, we’ll break down the most important advanced prompt engineering techniques, explain when to use each, and give you a practical mental model for applying them in real systems.

Why Advanced Prompt Engineering Techniques Matter

It’s tempting to treat prompting as a “better phrasing” problem: if the output is off, just tweak the instruction. For simple tasks, that’s often enough.

But in real products, you’re not asking the model to write a cute paragraph: you’re asking it to behave like a component in a system.

You want it to:

- follow constraints consistently,

- stay aligned with the task even when the input is messy,

- reason across multiple steps without losing the plot,

- and sometimes interact with tools (search, DBs, APIs, code execution) without hallucinating what those tools returned.

This is exactly where advanced prompt engineering techniques earn their keep.

Prompting is control, not vibes

If you’re a developer, you already understand this instinctively: structure drives reliability.

A JSON API with vague fields and inconsistent semantics becomes a debugging nightmare. The same thing happens with prompts. When you don’t provide scaffolding for reasoning, the model “fills in the gaps” in ways that look creative (but behave like nondeterministic failure modes).

Advanced prompt engineering techniques are essentially “control surfaces” for model behavior:

- Zero-shot and few-shot shape what the model should do by defining the task and showing the pattern.

- Reasoning techniques (like chain-of-thought, Tree of Thought, Skeleton of Thought) shape how it should think (especially for multi-step problems).

- Agentic techniques (like ReAct) shape how it should act when tools or external information are involved.

The goal isn’t to make the model smarter. The goal is to make the system more predictable.

The hidden costs of naive prompting

When teams stay in “tweak the instruction” mode too long, a few predictable problems show up:

- Inconsistency: The same prompt produces different quality depending on subtle changes in phrasing or input order.

- Brittleness: Add one more constraint (“also do X”) and the model drops half the requirements.

- Overlong outputs: The model rambles because it isn’t given a structure to stop.

- Latency and cost creep: You keep adding more prompt text, more retries, more post-processing, and more guardrails, because the prompt never became a reliable interface.

- Hallucination under pressure: When the task needs external facts or tool calls, naive prompts push the model to “make something up” rather than plan a retrieval step.

These issues aren’t just annoying. They’re operational risks.

If your system is customer-facing, inconsistency becomes a trust problem. If it touches workflows (support, ops, coding, finance), brittleness becomes a production incident.

What “advanced” really means in practice

In practice, “advanced” usually means one (or more) of these are true:

- The task has multiple steps.

The model needs to decompose, order actions, and keep intermediate state straight. - The task has competing constraints.

You want brevity and completeness, safe output and helpfulness, strict formatting and nuanced judgment. - The task requires planning.

You don’t just want an answer: you want an approach, a strategy, a checklist, or a decision tree. - The task depends on external context.

The model must retrieve information, use a tool, or follow a policy (and it needs to know when to do that versus when to respond directly). - The task must be reliable at scale.

A prompt that works “most of the time” is not a prompt you can ship.

The core idea: advanced prompt engineering techniques help you turn “a clever demo” into “a stable feature.”

A practical mental model: prompts as interfaces

A helpful way to think about this (especially if you build APIs) is:

- The prompt is your function signature.

- The examples are your test cases.

- The reasoning scaffolds are your internal implementation constraints.

- The tool protocol is your dependency boundary.

When you design prompts this way, you stop chasing outputs and start designing behavior.

And that’s the point of everything we’ll cover next: you’re going to learn a small set of patterns – zero-shot, few-shot, chain-of-thought, Tree of Thought, Skeleton of Thought, and ReAct – that you can mix and match to make models act more like dependable system components.

Next up, we’ll start with the foundation: zero-shot and few-shot prompting, and why “showing the pattern” is often the easiest reliability upgrade you can make.

Foundation (Zero-shot + Few-shot)

If you’re new to AI, here’s the fastest way to level up: stop thinking of prompts as “messages” and start thinking of them as interfaces.

The foundation of advanced prompt engineering techniques is simple: you either tell the model what to do (zero-shot) or you show it what “good” looks like (few-shot). Everything else we’ll cover later builds on that same idea (adding structure so the model behaves more predictably).

Zero-shot prompting: “Do the thing” (with constraints)

Zero-shot means you provide instructions without examples. It’s the default mode most people use.

It works great when:

- the task is familiar and well-scoped (summarize, classify, rewrite, extract),

- the input is clean,

- the output format is simple,

- correctness is easy to eyeball.

It fails more often when:

- the task has hidden edge cases,

- the output must follow a strict schema,

- the prompt contains multiple constraints that can compete,

- the model needs to infer the “pattern” you have in mind.

How to make zero-shot reliable (developer-style):

- State the goal in one sentence.

- Add constraints as bullets.

- Define the output contract (schema/template).

- Add negative constraints (what not to do).

- Add lightweight self-checks (validate format, handle missing data).

Zero-shot examples (from least to most complex)

1) Minimal instruction (works for easy tasks)

Summarize this text in 3 bullet points:

<PASTE TEXT>2) Add a user + format constraint (reduces rambles)

Summarize this text for an engineering manager.

Constraints:

- Exactly 3 bullets

- Each bullet ≤ 12 words

- No filler

Text:

<PASTE TEXT>3) Add structure + required fields (more predictable)

Summarize the design doc for an engineering manager.

Output format:

Goal:

Risks:

Next steps:

Constraints:

- Each line ≤ 20 words

- Do not include implementation details

Text:

<PASTE DOC>4) Add schema + missing-data rules (production-friendly)

Extract incident details from the text and output JSON only.

Rules:

- If a field is missing, use null.

- Do not invent values.

- Return valid JSON with double quotes.

Schema:

{

"incident_id": string|null,

"severity": "low"|"medium"|"high"|null,

"service": string|null,

"summary": string|null

}

Input:

<PASTE INCIDENT TEXT>5) Add constraints + validation + “don’t guess” guardrails (most reliable)

You are a strict extraction function. Extract the following fields and output JSON only.

Rules:

- Use null for missing fields.

- If severity is ambiguous, set severity to null.

- Do not guess services; only copy exact service names found in text.

- Output MUST be valid JSON. No trailing commas. No comments.

Validation checklist (apply silently before responding):

- JSON parses

- Keys match schema exactly

- severity is one of: low, medium, high, null

- summary is ≤ 160 characters

Schema:

{

"incident_id": string|null,

"severity": "low"|"medium"|"high"|null,

"service": string|null,

"summary": string|null

}

Input:

<PASTE INCIDENT TEXT>What the progression teaches: you’re not “sweet-talking” the model. You’re progressively tightening the interface: intent -> constraints -> contract -> error-handling -> validation.

Few-shot prompting: “Here’s the pattern (copy it)”

Few-shot prompting adds examples, so the model learns the mapping between input and output in-context.

For experienced developers, this should feel familiar: you’re essentially giving the model unit tests or golden examples and saying: “match this behavior.”

Few-shot helps most when:

- you want consistent tone/format,

- the task is domain-specific (“classify logs by our internal taxonomy”),

- you need stable output structure across messy inputs,

- you’re seeing “almost right” answers with zero-shot.

Few-shot samples (from least to most complex)

1) One example to lock the format (1-shot)

Rewrite the sentence to be more concise.

Example:

Input: "Due to the fact that the build failed, we had to rerun the pipeline."

Output: "Because the build failed, we reran the pipeline."

Now rewrite:

Input: "<PASTE SENTENCE>"

Output:2) Two examples to reduce ambiguity (2-shot)

Tag each ticket with exactly one label:

- BILLING

- BUG

- FEATURE_REQUEST

- HOW_TO

- ACCOUNT_ACCESS

Output: label only.

Example 1

Ticket: "Charged twice this month. Can you refund one?"

Label: BILLING

Example 2

Ticket: "App crashes when I click Export on iOS 17"

Label: BUG

Now tag this ticket:

Ticket: "<PASTE TICKET>"

Label:3) Add an edge-case example + rules (better boundaries)

Tag each ticket with exactly one label:

- BILLING

- BUG

- FEATURE_REQUEST

- HOW_TO

- ACCOUNT_ACCESS

Rules:

- If multiple labels fit, pick the most urgent user impact.

- If uncertain, output HOW_TO (default).

Output: label only.

Example 1

Ticket: "How do I change my email address?"

Label: HOW_TO

Example 2

Ticket: "Can't log in after enabling 2FA"

Label: ACCOUNT_ACCESS

Example 3 (edge case)

Ticket: "I can’t export invoices and I’m also locked out."

Label: ACCOUNT_ACCESS

Now tag this ticket:

Ticket: "<PASTE TICKET>"

Label:4) Add a strict output contract (structured output + examples)

Convert internal errors into user-safe messages.

Rules:

- No stack traces

- No internal service names

- Suggest one next step

- Output JSON only: {"title": "...", "message": "...", "next_step": "..."}

Example 1

Internal: "StripeError invalid_request_error: No such customer: cus_123"

Output:

{"title":"Payment issue","message":"We couldn’t process your payment details right now.","next_step":"Please re-enter your payment method and try again."}

Example 2

Internal: "DBTimeout: query exceeded 30s on orders table"

Output:

{"title":"Request timed out","message":"This is taking longer than expected.","next_step":"Please try again in a moment."}

Now convert:

Internal: "<PASTE ERROR>"

Output:5) Add multi-example coverage + negative example + self-check (most robust)

Normalize release notes into YAML items.

Output format (YAML):

- id: <short-slug>

type: feature|fix|perf|security

summary: <one sentence>

Rules:

- id must be kebab-case and ≤ 24 chars

- summary must be user-facing (no internal module names)

- If type is unclear, use "fix"

- Do not merge unrelated items

- Output YAML only

Example 1

Input: "Added retry to webhook delivery."

Output:

- id: webhook-retry

type: feature

summary: Added automatic retry for failed webhook deliveries.

Example 2

Input: "Fixed null pointer in billing export."

Output:

- id: billing-export-crash

type: fix

summary: Fixed a crash when exporting billing data.

Example 3 (perf)

Input: "Improved dashboard load time (p95 900ms -> 420ms)."

Output:

- id: dashboard-load

type: perf

summary: Improved dashboard load time for faster navigation.

Example 4 (security)

Input: "Rotated signing keys; tightened token validation."

Output:

- id: token-validation

type: security

summary: Strengthened token validation and key handling.

Negative example (what NOT to do)

Bad output (don’t copy):

- id: improved-dashboard-load-time-from-900ms-to-420ms-and-fixed-caching

type: perf

summary: did stuff in ui module

Self-check before responding:

- YAML parses

- id length ≤ 24

- type is one of: feature, fix, perf, security

- summary is user-facing and one sentence

Now normalize:

Input:

"<PASTE RELEASE NOTES>"

Output:What the progression teaches: few-shot isn’t “more text”: it’s better coverage: format lock-in -> ambiguity reduction -> edge cases -> strict contracts -> robust constraints + validation.

The real lever: examples beat explanations

A common beginner mistake is writing a longer and longer instruction block when results are inconsistent.

In practice, a single good example often outperforms five paragraphs of rules.

Why? Because examples implicitly encode:

- formatting,

- boundary decisions,

- what to do when data is missing,

- how strict or flexible you want the output,

- and what to prioritize when constraints conflict.

That’s why in advanced prompt engineering techniques, few-shot prompting is often the first “serious” reliability upgrade.

How many shots do you need?

There’s no universal number, but a useful rule of thumb:

- 1-shot: when you mostly need format consistency.

- 2–3 shots: when edge cases matter.

- 4–5 shots: when the model keeps drifting or the input distribution is noisy.

- More than 5: often diminishing returns (consider simplifying the task, tightening the output contract, or moving logic outside the model).

Also: prioritize coverage, not volume.

Two diverse examples (normal + tricky) usually beat five near-duplicates.

Picking examples like an engineer

If you’re going to invest in few-shot prompts, pick examples deliberately:

- Add one “boring baseline.”

- Include one “messy real-world” case.

- Use one “edge case you care about.”

- Keep outputs short and crisp.

- Make the examples consistent with your rules.

Few-shot prompting isn’t about showing off. It’s about reducing degrees of freedom.

A reusable template (mental model)

When you design prompts for production-ish use, it often helps to keep a consistent structure:

- Role / framing (optional, but useful)

- Task (one sentence)

- Constraints (bullets)

- Output format (schema/template)

- Examples (few-shot if needed)

- Now do it for this input (the actual request)

This style seems boring, and that’s exactly why it works.

Where this fits in the bigger picture

Zero-shot and few-shot are the baseline because they shape what the model is doing and what “correct output” looks like.

But once tasks involve multi-step reasoning (“plan, compare, decide”) or search/tool use, you need scaffolding that shapes how the model gets there.

That’s where the next section comes in: reasoning techniques like chain-of-thought, Tree of Thought, and Skeleton of Thought (and why they’re not all interchangeable).

Reasoning Techniques

Once you move past “summarize this” and “classify that,” you’ll hit a wall: the model can write an answer, but it can’t reliably think its way to an answer (at least not without help).

That’s where reasoning-oriented advanced prompt engineering techniques come in.

A useful mental model: in zero-/few-shot prompting, you mostly shape what the model should output. In reasoning techniques, you shape how it should get there (by adding just enough structure to keep it from skipping steps, missing constraints, or collapsing halfway through).

We’ll cover three patterns you’ll see everywhere:

- Chain-of-thought: step-by-step reasoning (linear)

- Tree of Thought: explore multiple branches (search)

- Skeleton of Thought: draft the structure first (plan -> fill)

Chain-of-thought prompting: guided, linear reasoning

What it is: You ask the model to reason in steps before producing the final answer.

When it helps:

- multi-step problems (tradeoffs, debugging, root cause analysis)

- constraint-heavy tasks (must satisfy X, Y, Z)

- tasks where “getting the process right” matters more than fancy wording

When it doesn’t:

- simple lookups or straightforward formatting

- tasks where you need the output but don’t want extra text (unless you constrain it)

Key upgrade move: separate thinking from answering. In practice, you often want the model to think internally but output only the final result (or a short rationale). That keeps answers clean and cheaper.

Chain-of-thought examples (from least to most complex)

1) Simple step-by-step math / logic

Solve the problem step by step, then give the final answer.

Problem:

If an API rate limit allows 120 requests per minute, how many requests is that per second?2) Constraint checklist (keeps requirements from getting dropped)

You are designing a caching strategy. Think step by step.

Requirements:

- cache invalidation must not break correctness

- must work across 3 regions

- implementation should be incremental (no rewrite)

Output:

1) Proposed approach (5 bullets max)

2) Risks (3 bullets)

3) What I’d measure to verify success (3 bullets)3) Debugging with a structured reasoning trace

You are debugging a production incident. Reason step by step.

Inputs:

- Symptom: intermittent 502s from the gateway

- Observation: spike correlates with deploys, but not every deploy

- Logs: "upstream reset before headers" and occasional "context deadline exceeded"

- System: gateway -> service A -> service B -> Postgres

Output format:

A) Most likely root cause (1 paragraph)

B) Top 3 hypotheses ranked with evidence

C) Fastest validation steps for each hypothesis

D) Mitigation plan for the next deploy windowTree of Thought prompting: explore multiple paths, then choose

What it is: Instead of one linear chain, you ask the model to generate multiple candidate approaches (“branches”), evaluate them, and pick the best.

When it helps:

- planning and architecture decisions

- ambiguous problems with multiple valid solutions

- “choose between strategies” tasks (tradeoffs matter)

- situations where a single reasoning path is likely to miss something

What makes it different from “just brainstorm”:

Tree of Thought isn’t “give me ideas.” It’s “generate options, evaluate them against criteria, then decide.”

Tree of Thought examples (from least to most complex)

1) Two options + quick selection

Generate 2 approaches to handle retries in a client SDK.

Then pick one and explain why in 3 bullets.

Criteria:

- simplicity

- avoids retry storms

- good defaults for most users2) 3 branches + scoring table

We need to add search to a product with ~2M records.

Create 3 solution branches:

A) Postgres full-text

B) Managed search (e.g., OpenSearch/Elastic)

C) Hybrid approach

For each branch, score 1–5 on:

- time to ship

- operational complexity

- relevance quality

- cost predictability

Then recommend one option and list the first 5 implementation steps.3) Multi-constraint architecture decision

We’re building an LLM-powered assistant inside an IDE.

Generate 4 branches:

1) pure chat (no tools)

2) retrieval-augmented (RAG) over docs

3) tool-using agent (search + repo indexing)

4) hybrid (RAG + tools + caching)

Evaluate each branch against:

- correctness under uncertainty

- latency

- cost per session

- security/privacy risk

- developer UX

Output format:

- Branch summaries (1 paragraph each)

- Evaluation matrix (bulleted scores)

- Final recommendation + why

- "If I’m wrong, here’s what would change the decision" (2 bullets)Skeleton of Thought prompting: outline first, then fill in

What it is: You force structure early by generating a “skeleton” (outline, headings, bullet plan) before writing the full response.

This is extremely useful for experienced devs because it’s basically: plan -> implement.

When it helps:

- long or complex answers (design docs, proposals, incident reports)

- anything that tends to ramble without structure

- outputs where completeness matters (you don’t want the model to forget a section)

Why it works: the model commits to a plan, which reduces mid-generation drift.

Skeleton of Thought examples (from least to most complex)

1) Outline then answer

First write a 5-bullet outline. Then write the final answer.

Question:

What are the tradeoffs between monolith and microservices?2) Fixed headings + fill (keeps it consistent)

Create a skeleton first (headings + 1 bullet each), then expand.

Topic:

Introduce rate limiting for a public API.

Skeleton must include:

- Goals

- Non-goals

- Proposed approach

- Edge cases

- Metrics

- Rollout plan

After the skeleton, expand each section to 1 short paragraph.3) Design doc skeleton with constraints

Write a design doc in two phases.

Phase 1: Skeleton only (no paragraphs)

- Use H2/H3 headings

- Under each heading, add 2–4 bullet points of what to cover

- Must include: problem, constraints, data flow, failure modes, security, observability, rollout, open questions

Phase 2: Expand

- Expand each H2 into 150–250 words

- Keep language concise and technical

- Include at least 3 explicit tradeoffs

Topic:

Add an async job system to handle webhook deliveries reliably.Choosing between these three (quick guide)

- Try chain-of-thought when you mostly believe there’s one “best path,” but the model tends to skip steps.

- Use Tree of Thought when there are multiple plausible paths and you want a deliberate selection.

- Choose Skeleton of Thought when output quality depends on coverage and structure (and you want to prevent rambling).

Next, we’ll shift from reasoning to action: agentic techniques (specifically ReAct), which is how you get models to think and use tools in a disciplined way.

Agentic Techniques

Reasoning techniques help the model think better. Agentic techniques help it do the right next thing: especially when the answer depends on external tools, retrieval, or multi-step interaction.

This matters because models are great at generating plausible text. They’re not automatically great at:

- knowing when they don’t know,

- deciding to fetch missing info,

- calling tools in the right order,

- or staying consistent across multiple actions.

Agentic prompting is how you turn “a smart text generator” into “a reliable workflow runner.”

What “agentic” means (in practical developer terms)

Think of an agentic prompt as a lightweight control loop:

- Observe the user input and current state

- Plan what to do next

- Act (optionally using tools)

- Update state / iterate

- Return a final result that matches an output contract

In other words: you’re not just asking for an answer. You’re defining a policy for how the model should behave.

This is where ReAct comes in.

ReAct prompting: Reason + Act (tools without hallucination)

ReAct is a prompt pattern that mixes reasoning (“what should I do next?”) with action (“call a tool / retrieve info / run a step”), repeatedly, until the task is complete.

When it helps:

- the model needs fresh or external facts

- the task requires tool calls (search, DB, code execution, APIs)

- the input is incomplete and you want the model to ask for what’s missing

- you care about reducing hallucinations by forcing “look it up” behavior

Core idea: don’t let the model pretend it knows. Make it explicitly choose between:

- answering now, or

- taking an action to get the missing information.

The prompt structure does the heavy lifting.

ReAct examples (from least to most complex)

1) “Ask clarifying questions before answering” (no tools)

Least complex agentic behavior: it’s still a single-turn response, but the model follows a decision rule instead of guessing.

You are a helpful assistant. Before answering, check if any critical info is missing.

Rules:

- If the request is ambiguous, ask up to 3 clarifying questions.

- If it is clear, answer directly.

- Keep the final answer under 8 sentences.

User request:

<PASTE REQUEST>2) Tool-gated lookup (retrieve before answering)

More agentic: the model must decide to retrieve facts, then answer. You can map “TOOL: search” to whatever tool your system provides.

You are an assistant that can use a search tool.

Policy:

- If the user asks for up-to-date info or anything factual you are unsure about, you MUST use the tool.

- Do not guess dates, versions, prices, or current events.

- After using the tool, answer concisely and cite what you found.

Interaction format:

Thought: (private)

Action: TOOL:search(query="...")

Observation: (tool result)

Final: (answer for the user)

User question:

<PASTE QUESTION>3) Multi-step tool workflow with state + stopping condition

Most complex agentic behavior: the model plans, executes multiple actions, keeps state, and stops when acceptance criteria are met.

You are an agent that can use tools: search, code, and database.

Goal:

Generate a weekly report on API errors and propose fixes.

Constraints:

- Use tools whenever data is required.

- Never invent numbers.

- Keep a running state: {time_range, top_errors, suspected_causes, proposed_fixes}

- Stop when: top_errors has 5 items AND proposed_fixes has 5 items.

Workflow:

1) Plan the steps.

2) Query database for error counts in {time_range}.

3) For each top error, search internal docs or run code to correlate to recent deploys.

4) Produce fixes prioritized by impact and effort.

Output format (final):

- Time range:

- Top 5 errors (count, % change):

- Root-cause hypotheses:

- Proposed fixes (impact/effort):

- Next measurements:

Start with:

time_range = last 7 daysWhy ReAct reduces hallucinations

A model hallucinates most when it feels pressured to “complete the story” without enough information.

ReAct changes the incentives:

- it normalizes saying “I need to look that up,”

- it forces an action step when facts are missing,

- and it separates getting information from presenting an answer.

In production, this is the difference between:

- “it sounded right” and

- “it was verified by a tool.”

Design tips for agentic prompts (what actually works)

- Make tool use explicit and mandatory for certain cases.

“If you need current info, you MUST call search.” - Define a stop condition.

Without it, agents can loop or overthink. - Use output contracts.

The final response should still look like an API response: consistent shape, predictable fields. - Prefer small, composable steps.

“First plan, then execute” beats “do everything at once.” - Fail safely.

Add rules like: “If the tool fails, explain what you can do without it.”

How agentic fits with the earlier techniques

In real systems, you rarely use these in isolation:

- Few-shot to lock formatting and behavior

- Skeleton of Thought to plan the response structure

- Tree of Thought to explore tool strategies or debug paths

- ReAct to drive tool-using execution reliably

Next, we’ll make this practical: how to choose the right technique for the job (and avoid overengineering prompts when a simpler pattern would do).

Choosing the Right Technique

By now, you’ve seen the toolbox: zero-shot, few-shot, chain-of-thought, Tree of Thought, Skeleton of Thought, and ReAct.

The tricky part isn’t knowing what they are. It’s knowing when to use which one, without turning every prompt into a manifesto.

Here’s a practical way to choose the right advanced prompt engineering techniques based on the shape of the problem.

Start simple: don’t over-engineer

A lot of teams jump to “reasoning prompts” too early because the model gave one bad answer.

Before you add complexity, ask two questions:

1) Is the task clear and bounded?

2) Is the output contract strict (format/schema)?

If the answer is “yes,” start with zero-shot and tighten the contract. You’ll often get 80% reliability with 20% effort.

A decision checklist (the one you actually use)

Use this as your mental switchboard:

1) Is the task straightforward and repeatable?

- Yes: Zero-shot

- No: keep going

Typical “yes” tasks:

- summarization with a fixed format

- simple classification

- extraction into a schema

- rewriting with a tone constraint

Upgrade path: zero-shot -> add constraints -> add output template.

2) Is the model “mostly right” but inconsistent?

- Yes: Few-shot

- No: keep going

Few-shot is your best move when you can’t fully describe the rule, but you can show it.

Common signals you need few-shot:

- formatting drift (sometimes follows, sometimes doesn’t)

- category boundary issues (“BUG vs FEATURE” flips)

- tone inconsistency (“too salesy,” “too cautious,” “too chatty”)

- edge cases behave unpredictably

Upgrade path: 1 example -> add an edge-case example -> add a tricky/ambiguous example.

3) Does the task require multi-step reasoning?

- Yes: Chain-of-thought or Skeleton of Thought

- No: keep going

Now you’re in reasoning territory. Choose based on what “breaks”:

- If the model skips steps or drops constraints: Chain-of-thought

- If the model rambles or forgets sections: Skeleton of Thought

A simple rule:

Chain-of-thought = correctness through steps

Skeleton of Thought = completeness through structure

4) Are there multiple plausible approaches with tradeoffs?

- Yes: Tree of Thought

- No: keep going

Tree of Thought is for “choose a strategy” work:

- architecture decisions

- selecting a migration approach

- comparing frameworks / tradeoffs

- deciding a debugging plan

If you want the model to stop pretending there’s one obvious answer, Tree of Thought forces it to explore options and justify a pick.

5) Does the model need external info or tools?

- Yes: ReAct

- No: you’re probably done

If the answer depends on:

- current facts

- internal docs

- database queries

- code execution

- calling APIs

…then the core risk is hallucination. ReAct is how you force “retrieve, then answer” instead of “guess confidently.”

A quick mapping: failure mode -> technique

- “It answers, but misses requirements.”: Chain-of-thought

- “It rambles and forgets sections.”: Skeleton of Thought

- “It’s inconsistent across similar inputs.”: Few-shot

- “It chooses a random strategy each run.”: Tree of Thought

- “It makes up facts / numbers / citations.”: ReAct

- “It’s fine, just needs a tighter format.”: Zero-shot + output template

Next, we’ll talk about the ways teams accidentally sabotage themselves: the most common mistakes that make prompts brittle, expensive, or unreliable (even when the technique is “correct”).

Common Mistakes

Most prompt failures aren’t “the model being dumb.” They’re interface problems: unclear constraints, missing contracts, or messy scope.

Here are the mistakes that show up most often with advanced prompt engineering techniques (and the quick fixes).

1) Stating goals, not constraints

Symptom: It follows the vibe, misses requirements.

Fix: Turn requirements into hard rules (limits, must-include items, forbidden items).

2) No output contract

Symptom: Formatting drifts; parsing breaks.

Fix: Always define a template/schema (or “label only”).

3) Too many tasks in one prompt

Symptom: It does one thing well and drops the rest.

Fix: Split into steps (extract -> decide -> generate artifacts).

4) Weak few-shot examples

Symptom: Works on clean inputs, fails in the wild.

Fix: Use representative examples: normal + messy + edge case.

5) Asking for reasoning without controlling output

Symptom: Long explanations, higher cost, noisy responses.

Fix: “Think step by step, output only final answer” (or cap rationale).

6) Tree of Thought without criteria

Symptom: Options are listed, decision feels random.

Fix: Add explicit evaluation criteria (latency, cost, risk, time-to-ship).

7) ReAct without tool rules

Symptom: Hallucinated “tool results.”

Fix: Make tool use mandatory for facts; “never invent numbers”; handle tool failures.

8) No stop condition (agents that loop)

Symptom: Overthinking or endless tool calls.

Fix: Define a stopping rule (N tool calls, N validated items, or confidence threshold).

9) Prompts not treated like code

Symptom: Regressions, no one knows what changed.

Fix: Version prompts, keep test cases, track validity/latency/cost.

Next: a realistic Future Outlook. What’s becoming easier, what still matters, and where prompting is heading.

Future Outlook

A lot of “prompt engineering” advice ages quickly, because models keep getting better. But the core problem doesn’t go away: you’re still integrating a probabilistic system into deterministic software.

So the future isn’t “no more prompts.” It’s fewer clever prompts and more reliable interfaces.

1) Prompting will look more like product engineering

Teams are already moving from “one big prompt” to:

- smaller prompt components,

- reusable templates,

- and prompt versioning with test cases.

In other words: prompts become a maintained layer in your stack, not a one-off artifact.

2) Output contracts will matter more than phrasing

As models improve, “say it nicely” matters less. What still matters a lot:

- strict schemas (JSON/YAML),

- predictable structure,

- and clear constraints.

That’s the part that integrates with code (and it’s the part that breaks first in production).

3) Tool use becomes the default for anything factual

As agent systems mature, you’ll see a clearer split:

- Models generate reasoning and language

- Tools provide truth (search, DB, code, source-of-record systems)

ReAct-style policies (“retrieve, then answer”) will become standard because hallucination isn’t a prompt problem: it’s a systems problem.

4) Reasoning scaffolds shift from “make it think” to “make it dependable”

Chain-of-thought, Tree of Thought, and Skeleton of Thought won’t disappear. But they’ll be used less as “boost intelligence” and more as:

- guardrails (don’t skip steps),

- coverage tools (don’t forget sections),

- decision tools (evaluate tradeoffs explicitly).

The goal stays the same: fewer silent failures.

5) Evaluation becomes non-negotiable

The teams who win here aren’t the ones with the fanciest prompts. They’re the ones who treat LLM behavior like any other system behavior:

- define what “correct” means,

- measure it,

- and catch regressions early.

That’s the real maturity curve: from prompt tweaking to prompt + eval + iteration.

Where this leaves you

If you remember one thing: advanced prompt engineering techniques are less about wordsmithing and more about designing reliable interfaces for reasoning and action.

Start with a clear contract. Add examples when outputs drift. Add reasoning structure when steps matter. Add ReAct when tools and truth matter.

That’s how you go from “it works in a demo” to “it holds up in production.”

I invite you to test those techniques with the help of this article: Chat Completions API – Unleashing Unlimited Creativity With ChatGPT

Thank you for reading this article!

0 Comments